This page has been archived and is being provided for reference purposes only. The page is no longer being updated, and therefore, links on the page may be invalid.

Read the magazine story to find out more. |

|

Deconstructing a Deadly Mold, Gene by Gene

By Erin PeabodyOctober 16, 2006

Fungi: Can't live with them, can't live without them.

While many of these tiny spore-producers are lauded for their industriousness (think penicillin, yeast for leavened bread, and mold-enhanced delicacies like Roquefort and blue cheeses), it seems there are just as many noxious fungi out there ready to contaminate food, houses—even the air we breathe.

And no mold is as dark a character as Aspergillus flavus, which is why scientists with the Agricultural Research Service (ARS) and their collaborators are scrutinizing this fungus, one gene at a time.

A. flavus can be terribly destructive. With an affinity for corn, peanuts, cottonseed and tree nuts such as almonds and walnuts, it can plague vast acreages of crops in the United States and threaten food and animal feed security worldwide.

What's so dangerous about A. flavus are its deadly toxins, known collectively as aflatoxin. These fungal poisons are the second leading cause of aspergillosis in humans. Considered to be among the most potent carcinogens in nature, they've also been linked to some forms of cancer.

Because of the risks associated with aflatoxin, the Food and Drug Administration has put safeguards in place to protect consumers. But federal researchers—like ARS geneticist Jiujiang Yu—would like to find ways to keep toxic fungi from occurring in the first place.

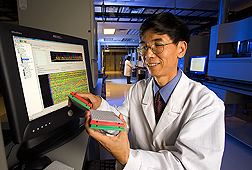

Yu, who works at the ARS Southern Regional Research Center in New Orleans, La., was part of a team of scientists who recently sequenced a strain of the A. flavus fungus. Along with ARS researchers Ed Cleveland and Deepak Bhatnagar, Yu collaborated on the project with North Carolina State University's Gary Payne and William Nierman of The Institute for Genomic Research in Rockville, Md.

One of the team's primary goals is to pinpoint which of the fungus' 13,000 genes regulate toxin production. They'd like to disable them so they can rob the fungus of its poison-making machinery.

Read more about this and other food safety research in the October 2006 issue of Agricultural Research magazine.

ARS is the U.S. Department of Agriculture's chief scientific research agency.