| Bee Blog |

|

June 28, 2023: Bumblebees

Enjoy this information about Wisconsin bumblebees, written by Floréal.

Overview

With their fuzzy bodies and characteristic black, yellow and sometimes orange patterning, bumblebees are some of the most well-recognized and charismatic species of bee. Wisconsin is home to seventeen species of bumblebees, including the federally endangered rusty-patched bumblebee (Bombus affinis). Unlike most bee species, bumblebees are most diverse in temperate regions, making Wisconsin the perfect place for them to call home.

Rusty-patched bumblebee. ©Wisconsin Pollinators

Biology

Bumblebees are relatively large, social bees. The fuzzy hairs that cover their bodies are not only morphologically unique, they also make them great pollinators as pollen is easily picked up and deposited. Foraging bumblebees have a corbicula, also called a pollen basket, on their hind legs. This specialized structure helps them collect large quantities of pollen to bring back to their nests. Male bees and parasitic bumblebees, known as cuckoo bumblebees, do not have pollen baskets as they do not forage for the hives. Cuckoo bumblebees enter the established colony of another species and lay their eggs, which allows their young to be raised without the need to forage for them. Uniquely, bumblebees perform “buzz pollination” in which they land on a flower and vibrate their wings to release pollen. This method of pollination is especially important for crops that do not easily release pollen, such as tomatoes and blueberries.

Bumblebee with pollen basket. ©Rusty Burlew

Lifecycle

Bumblebees build annual colonies, which means that unlike honey bees, the hives will only exist for one season. In the spring, the bumblebee queen, also known as a gyne, emerges from hibernation and begins her search for a suitable nest site such as an abandoned rodent burrow or birdhouse. Once she has found the right place, she leaves to forage pollen and nectar to store in wax pots. When sufficient food stores are acquired, she begins laying eggs and the newly emerged female bees feed on the nectar and pollen. As soon as the bees are developed enough to leave the nests, they take over foraging duties so that the queen can continue laying eggs and creating new worker bees. A colony of bumblebees can have 100-300 workers at a given time. In the fall, the queen lays eggs that will turn into new queens as well as male drones. The drones and new queens leave the nest to mate with different hives and the old queen, workers, and drones die. The new queens hibernate in preparation for beginning the cycle again the following spring.

Inside a bumblebee nest. ©K.P. McFarland

Threats

Unfortunately, like most species of native bees, bumblebees are currently facing alarming population declines due to a number of threats. Because of their hairy bodies, bumblebees are especially sensitive to increasing temperatures due to climate change. Similarly, drought conditions decrease key food resources as flowering plants require water to produce nectar. Habitat loss due to development and lawn management, as well as pesticide use and disease all contribute to declining bee populations.

Conservation

Luckily, there is hope for Wisconsin bumblebees! While rare, sightings of the endangered rusty-patched bumblebees have led to changes in land management protocols and strategies. If you think you’ve spotted a rusty-patched bumblebee, be sure to snap a picture and pass it along to the DNR.

There are many things that you can do to help your local bees. Planting spring ephemerals such as dutchman’s breeches provides queen bees with the pollen and nectar they need to start a strong hive. Consider planting native keystone plants that will provide bees and other insects with important resources, such as goldenrod, sunflowers, and asters. Avoid the use of pesticides and if you must spray, be sure to do so when plants are not in flower. In the fall, leave leaf litter and plant stalks as this will provide hibernating queens with the protection they need to survive the winter. Creating or providing adequate habitat is essential to the conservation of bumblebees in Wisconsin.

May 26, 2023: Leafcutting bees

We are currently conducting an experiment with alfalfa leafcutting bees in a greenhouse setting. Here is a little bit of information about leafcutting bees, written by Floréal Crubaugh.

Left photo © Sharp-Eatman Nature Photography. Right photo © Keeping Backyard Bees.

Leafcutting bees are a fascinating and important bee species. These bees belong to the genus Megachile, which includes a variety of solitary nest-building species such as mortar bees and resin bees. Only a little smaller than the average honeybee, leafcutting bees are easily identifiable by their relatively large heads and white stripes. They have large mandibles, and females have sharp teeth for neatly cutting leaves. Many species of leafcutting bees are native, and they can also exist as a managed agricultural species.

These bees are especially efficient pollinators due to how they collect pollen. Instead of collecting pollen in “baskets” on their legs like honeybees and bumblebees, leafcutting bees exclusively collect pollen in the hairs on the underside of their abdomen. Because of this, it is easy for pollen to spread between plants when the bee lands on a flower to collect pollen or nectar. A leafcutting bee will pollinate about 95% of the flowers it visits, whereas a honeybee only pollinates about 5%. Not only are leafcutting bees built for pollinating, they’re also hard workers! The efforts of one leafcutting bee is roughly equal to that of 20 honeybees. Since leafcutting bees are so good at pollinating, many crop producers will use them to increase their yields for crops such as alfalfa, blueberries, and sunflowers.

Leafcutting bees earned their name by cutting out circular patches of leaves to build nests. These leaf cutouts are used to line the inside of long, tubular nests that serve as a nursery for larvae. When a bee is ready to build her nest, she will find a small hole inside a dead log, beetle tunnel, or disturbed soil. Once she has located a suitable spot, the bee will use the leaf circles to create a layered capsule for her eggs. Each egg receives a little bit of pollen and is sealed with a sheet of leaf material. The bee will continue laying her eggs and layering them with pollen and leaves until the hole is filled. When the first egg hatches, the larva will eat its way through the pollen and dried leaves until it emerges from the nursery.

Left photo: Leafcutting bee with leaf. Right photo: Leafcutting bee cocoons. Photos © Missouri Dept of Conservation

Like all bee species, leafcutting bees face imminent population declines due to climate change, pesticide usage, and loss of habitat. To support healthy bee populations in your backyard, consider installing a bee box with bamboo sticks or holes to provide space for leafcutting bees to build their nests. Consider reducing or stopping pesticide application. While these bees can cause leaf damage, the damage is not severe enough to harm a plant and pesticide application will not deter them. Finally, be sure to plant a variety of native flowering plants that will provide pollen and nectar throughout the season.

May 2, 2023: The Buzz about Bees

Our part-time technician Floréal Crubaugh wrote this article about bees for a class, and we thought this would be a great place to share it!

Green sweat bee ©BugGuide. Rusty patched bumble bee ©Wisconsin Pollinators. Andrena ©Missouri Department of Conservation.

Imagine going your local supermarket and one-third of the food is gone. There are no apples, melons, or almonds. Imagine fewer flowers blooming in spring. Imagine no pumpkins on Halloween. Sound bleak? That is our world without pollinators.

At a time when pollinator species are in decline, we are dedicated to educating the public about the importance of bee species and the ways in which they provide essential pollination services to produce food and ensure healthy plant populations. We need bees, and bees need us to conserve and protect them.

Importance of Native Bees

While the importance of honey bees is well known, the significance of native or “wild” bees is less familiar to most people. While they don’t produce honey or live in large hives, their importance in maintaining healthy ecosystems cannot be overstated. In addition to helping honey bees pollinate crops, native bees are responsible for pollinating 80% of the world’s flowering plant species. Many of these plant species have highly specialized relationships with the bees they rely on. For example, a species of mining bee that lives in the Iberian Peninsula only visits one type of plant, the curl-leaved rock rose . Because plant-pollinator relationships are so interdependent, losing a pollinator species could also result in the loss of a plant species. Despite their essential nature, many native bee species are severely threatened. The rusty patched bumble bee, a species native to North America, has declined 87% in recent history.

Threats

The single greatest threat native bees are facing is the ubiquitous loss of habitat due to agricultural intensification, urbanization, and the loss of native plant species. Reducing suitable pollinator habitat means the loss of essential food resources and nesting sites. Instead of building large colonies, many native bees are solitary and lay eggs in soil, sand, or leaf litter. Eliminating important nest substrate by pouring asphalt, tilling, or raking leaves makes it harder for bees to find suitable nesting sites. Managing land in a way that populates an area with wind or self-pollinated plants such as grass and corn can eliminate important food forage, forcing hungry bees to fly further for flowering plants to collect nectar and pollen.

Pesticides are another significant problem for bees. Many pesticides that are applied in urban or agricultural environments contain chemicals called neonicotinoids. These chemicals are poisonous to bees and contaminate the pollen and nectar that they feed on, causing mass die-offs or significantly changing behavior and life cycles. The EPA recently recommended a set of guidelines to help diminish the risk of pesticides to pollinators, including not spraying flowering plants and better application strategies to ensure pesticides are only affecting their targets.

How to Help

Pollinators face immense threats with catastrophic implications for our ecosystems and agricultural productivity. Fortunately, there are numerous ways in which you can help support pollinator populations and ensure healthy local ecosystems

The most important thing you can do is use your yard to provide pollinator habitat. This can involve low-effort measures such as participating in No Mow May or simply mowing less. Reducing or eliminating mowing ensures that bees have access to pollen and nectar from flowering plants such as clover and dandelions. Another lawn-management practice that can help pollinators involves planting native flowers, creating much needed habitat for bees to forage throughout the season. Providing nesting habitat for solitary bees in the form of bee houses alleviates the loss of nesting substrate and ensures healthy reproduction rates.

Creating adequate pollinator habitat won’t be sufficient to help pollinator populations unless we also curtail our use of pesticides. Supporting local, organic-certified farms guarantees that crops are not grown in a way that creates disproportionate harm to the pollinators they rely on. Transitioning common neonicotinoid-containing commercial pesticides to organic or neonicotinoid-free pesticides will mean that if bees visit your garden they will not be inadvertently poisoned. Neem oil is a popular alternative to traditional pesticides for keeping unwanted bugs away.

April 17, 2023: Science Expeditions

We participated in the UW Science Expeditions event this past weekend! Our Exploration Station was named “Why all the buzz about bees?”

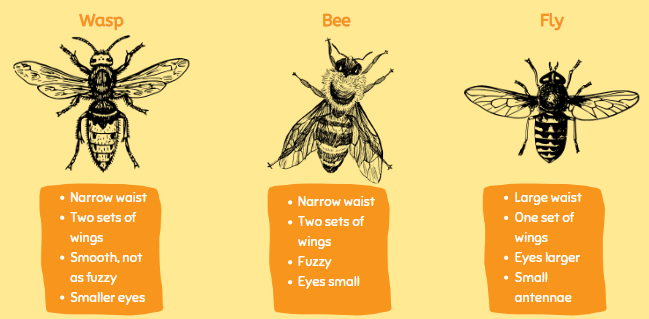

We had lots of bee and wasp specimens for people to examine, and had many interesting conversations about bees, insects in general, bee and wasp stings, and attracting bees to your yard. Visitors learned to distinguish between bees, wasps, and flies in our “A Bee or Not A Bee?” game. Bees and wasps are closely related but are different groups of insects, and Syrphid flies (also called hoverflies) are very convincing bee-mimics.

Here are some tips to distinguish between wasps, bees, and flies:

We also had a display with different food items to facilitate conversations about pollination. Many fruits and vegetables are bee-pollinated, such as apples, cherries, raspberries, and tomatoes. Tomatoes are buzz-pollinated by bumble bees and carpenter bees (which look like large bumble bees) – while the bee is drinking nectar from a flower it vibrates its body to knock pollen off of the flower. A fruit that does not need to be pollinated is bananas! The bananas we eat are actually unpollinated. When a banana flower is pollinated it produces a dry fruit full of seeds. Cocoa is pollinated by midges (a type of fly) and coffee does not need to be pollinated, but when it is it produces more and better quality beans.

If you didn’t make it to the Science Expeditions this year, maybe we’ll see you next year! And don’t forget to check back here soon for another post about bees.

All photos courtesy of Molly Mabin.