This page has been archived and is being provided for reference purposes only. The page is no longer being updated, and therefore, links on the page may be invalid.

Hidden Elm Population May Hold Genes to Combat Dutch Elm Disease

By Kim Kaplan

March 30, 2011

WASHINGTON—Two U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) scientists may have discovered "the map to El Dorado" for the American elm—a previously hidden population of elms that carry genes for resistance to Dutch elm disease. The disease kills individual branches and eventually the entire tree within one to several years.

It has been accepted for 80 years that American elms (Ulmus americana) are tetraploids, trees with four copies of each chromosome. But there have also been persistent but dismissed rumors of trees that had fewer copies—triploids, which have three copies of chromosomes, or diploids, which have two copies.

Now botanist Alan T. Whittemore and geneticist Richard T. Olsen with USDA's Agricultural Research Service (ARS) have proven beyond question that diploid American elms exist as a subset of elms in the wild. Their findings will be published in the April edition of the American Journal of Botany. Whittemore and Olsen work at the U.S. National Arboretum operated by ARS in Washington, D.C.

American elms once lined the country's streets and dominated eastern forests until they succumbed by the millions after Dutch elm disease arrived in the United States in 1931. Yet elms are still one of the most important tree crops for the $4.7 billion-a-year nursery industry, especially since the introduction of a very few new trees with some tolerance to the disease. American elms remain popular because of their stately beauty, their rapid leaf litter decay and their ability to stand up to city air pollution.

It was one of the disease-tolerant elm trees—Jefferson, released jointly by ARS and the National Park Service in 2005—that put Whittemore and Olsen on the trail of the diploid.

"Jefferson is a triploid. To get a triploid elm, we thought there had to be a diploid parent out there somewhere in the wild that had crossed with a tetraploid," said Whittemore.

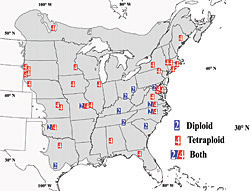

To settle the question, the two scientists tested elm trees from across the species' eastern and central U.S. range. About 21 percent of the wild elms sampled were diploid; some grew in stands with tetraploids, while others were larger groupings of diploids.

The small amount of genetic data now available suggests that at least some tetraploid and diploid elm populations have diverged significantly from one another, which strengthens the possibility of the diploid trees having genes for disease resistance that the tetraploids don't have, Whittemore said.

"We can't say yet whether this is a distinct race of U. americana or if we are really talking about a separate species," he said. "That's a job we will tackle this summer."