This page has been archived and is being provided for reference purposes only. The page is no longer being updated, and therefore, links on the page may be invalid.

| Read the magazine story to find out more. |

|

|

New Imaging Technique Leads to Better Understanding of Freezing in Plants

By Dennis O'Brien

October 27, 2014

A U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) agronomist in North Carolina has used an imaging technique he developed to uncover fresh details about what happens to oats when they freeze. The work by David P. Livingston, who is with the USDA’s Agricultural Research Service (ARS) in Raleigh, has implications for growers.

Oats, for instance, won’t grow in many northern areas because of cold temperatures, and Livingston’s technique is helping scientists understand how ice forms in oats. That could help breeders develop hardier varieties of oats and expand their range. Livingston also has used the technique to examine wheat, barley, rye and corn.

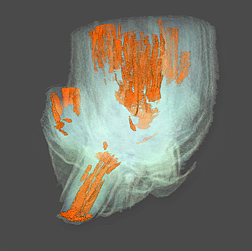

The technique involves making high-resolution digital photos of slices of plant tissues and using commercial software to create a 3-dimensional perspective. The resulting images give added depth to plant structures, above and below ground. Livingston’s images are somewhat similar to images produced by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography (CT) scans. But, Livingston can create them from much smaller tissue samples and at a lower cost.

In recent work, Livingston, who is with the ARS Plant Science Research Unit in Raleigh, stained frozen tissue samples of oat plants and took 186 sequential images as part of a study to see how they would react to freezing temperatures in the soil. He then aligned the images and used imaging software to clear away the background colors so he could focus on cavities formed by ice crystals in the crown tissues of the oats. He then compared images from frozen plants with those from plants kept at normal temperatures.

The images revealed that when oats freeze in winter, ice forms in the roots and portions of the crown, which lies just below the soil surface and connects the roots to the stalk. The images also showed that the ice in the crown is limited to its lowest and upper level parts, apparently leaving the middle portion ice-free—at least free of crystals big enough to visualize. The crown is critical to growth because that is where the plant generates new tissue if it survives the winter cold. The results were published in 2014 in Environmental and Experimental Botany and included a video available at /is/video/mov/freezeplants.mov.

Read more about this work in the October 2014 issue of Agricultural Research magazine.

ARS is USDA’s chief intramural scientific research agency, and this research supports the USDA priority of promoting agricultural sustainability.