First Meal is Vital for Calf and Piglet Survival

The first meal of their lives may well determine the fate of calves and piglets; if they don't get what they need quickly, the newborns may not survive to weaning age, said two scientists with the Agricultural Research Service (ARS).

Colostrum is a vital nutrient that mothers provide in the first feedings that newborn farm animals must have within 24 hours of birth. Calves and piglets are born without much of an immune system, and colostrum provides them with a rich dose of antibodies, or immunoglobulins.

"It is very important for a calf to receive protective antibodies from its mother," said Mike Clawson, research molecular biologist at the ARS Genetics, Breeding, and Animal Health Research Unit in Clay Center, NE. "Those antibodies can protect the calf from the same pathogens its mother was exposed to long enough for its own immunity to develop." Clawson's research includes the genomic aspects regarding the failure of passive transfer of colostrum antibodies in cattle.

A Hereford cow nurses her calf. Calves that do not receive enough colostrum face increased risk of disease and death. (Bruce Fritz, K3910-15)

A Hereford cow nurses her calf. Calves that do not receive enough colostrum face increased risk of disease and death. (Bruce Fritz, K3910-15)

Calves and piglets that do not receive antibodies from their mothers are at profound risk for disease and death. Before they are born, their mothers concentrate immunoglobulins in colostrum, which is essentially a first milk. Calves and piglets typically nurse shortly after birth, and the ingested antibodies are ultimately transported to their circulatory system.

Timing is everything in this process because shortly after delivery, the mother's production of immunoglobulin drops by 90 percent. In roughly that same time span, newborns lose the ability to take in the benefits of colostrum.

"The newborn gut is permeable to large molecules at birth, but within 24 to 48 hours it becomes impermeable to them," said Jeff Vallet, ARS national program leader for food animal production in Beltsville, MD. "Even if we were to provide colostrum to older newborns, absorption of the immunoglobulins is reduced or eliminated." Vallet's research involved developing the "immunocrit" testing system to determine if a piglet received enough colostrum from its sow.

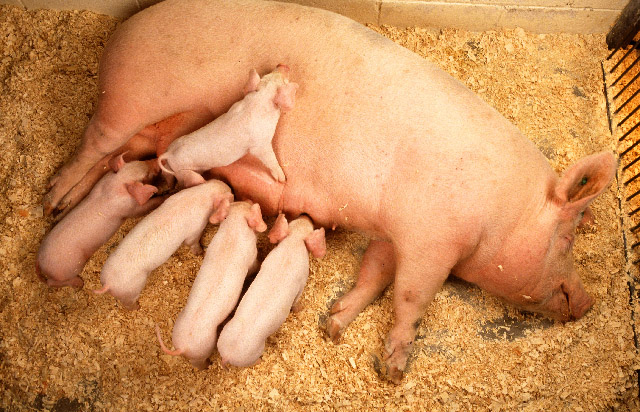

A sow and her nursing piglets. If piglets do not receive enough colostrum in the first day of life, they face increased chances of illness and death. (Keith Weller, k7976-2)

A sow and her nursing piglets. If piglets do not receive enough colostrum in the first day of life, they face increased chances of illness and death. (Keith Weller, k7976-2)

According to Clawson, colostrum deprivation is the greatest risk factor for a calf to become sick or die before weaning. "Calves that do not receive colostrum are 50 times or more likely to die in the first 3 weeks of life," he said. Calves that do not receive adequate colostrum yet manage to survive past weaning are at elevated risk for developing disease later in their lives.

Colostrum is even more important for piglets, Vallet said. Small piglets are very sensitive to a lack of colostrum, and their mortality rate increases as high as 80 percent. Larger piglets have more energy reserves and may survive, but they are more susceptible to diseases. In addition, the lack of colostrum impairs gut and uterine development, which reduces feed and reproductive efficiency.

Farmers, ranchers and veterinarians can determine the colostrum status of their newborn livestock through the simple immunocrit blood test. If the newborns lack immunoglobulins, they may be hand-fed commercially available colostrum replacements or supplements.

A 2016 paper published in Europe studied the cost of colostrum antibody deficiency to calves. That study estimated a loss of about $68 and $91, respectively, for each dairy and beef calf. In the United States, over 20 percent of beef cattle calves and 19 percent of dairy calves suffer from colostrum deprivation. Preweaning mortality costs the U.S. swine industry an estimated $1.6 billion each year, and one of the contributing factors is deficient colostrum intake by piglets. – by Scott Elliott, ARS Office of Communications