Fighting a Ferocious Foe: ARS Seeks a Fire Ant Fix

|

Robert Vander Meer is the Research Leader for the Imported Fire Ant and Household Insects Research Unit in Gainesville, FL. |

Welcome to Under the Microscope, Dr. Vander Meer.

UM: Are fire ants native to the U.S.?

RV: The black imported fire ant, Solenopsis richteri, was accidentally imported from Argentina into the port of Mobile, AL, in the early 1900s, followed by the red imported fire Ant, Solenopsis invicta, in the 1930s (also into the Mobile, AL port) from Brazil or northern Argentina. S. richteri is more adapted to cooler climates, while S. invicta is more tropical/subtropical.

Working with colleagues, I found that the two can intermate, creating reproductively viable hybrids. The hybrid is morphologically indistinguishable from S. richteri, so there are now three types of imported fire ants – the two species and their hybrid. Over the past 80+ years, the imported fire ants have been accidentally transported, through human activities like infested plant nursery stock. Climate conditions have created two weather-dictated fire ant bands with S. invicta in the warmer Southern tier, gradually giving way to the more cold-tolerant hybrid.

There are also native fire ants in the southern U.S. Solenopsis geminata (the tropical fire ant) was spread during the 15th – 18th centuries from the U.S. gulf coast to many tropical/subtropical areas of the world via shipping. Other types are not common. The invasive types, however, are now found throughout the southeastern U.S.

Widely disliked for their venomous, painful stings, fire ants have spread across much of the southern United States. (Photo by Scott Bauer)

Widely disliked for their venomous, painful stings, fire ants have spread across much of the southern United States. (Photo by Scott Bauer)

UM: Why are fire ants a problem?

RV: Fire ants negatively affect crops, ecosystems, and humans. They pose a significant threat because they are prolific breeders and so far, not easily controlled at any significant scale. The red imported fire ant is a specialist of disturbed habitats, and humans are specialists in creating disturbed habitats. A mature fire ant colony can contain 250,000 workers; usually a single queen can maintain the high worker numbers for 5-7 years. The queen can lay up to 3,000 eggs per day, which drives the large number of workers and the colonies’ continuous need for food. The ants are omnivores, taking advantage of all dead or weak animals, newly hatched birds, turtles; endangered species are not spared. The ants cause problems across multiple areas:

- Humans: 15% of the population are susceptible to developing hypersensitivity to fire ant venom. This is an under-studied and evaluated area! Life-threatening allergic response events are not uncommon.

- Crop yield losses: In the seven Southern states with fire ant infestations, losses to soy farmers average around 10% of the crop value. In corn crops, it’s 25% as the ants consume germinating seeds and damage young seedlings. There are significant losses across other sectors, too; in citrus, for instance, the ants chew bark and cambium to obtain sap, and in the process, “girdle” the trees, removing bark all the way around the trunk, which kills the tree.

- Soy/nitrogen/soil fertilization: Farmers usually count on soybeans to add nitrogen back into the soil, due to nitrogen-fixing bacteria associated with plant roots. Fire ant venom has antimicrobial activity and negatively affects the nitrogen-fixing bacteria. This negates the soil fertilization advantage of planting soybeans.

- Harm to livestock: The fire ants are always opportunistic! Calves and other newborn animals are at risk from fire ants, which often get into the eyes of the animals, where they sting, often causing blindness.

- Ecosystems: Birds that have nests on the ground or in bushes are at risk of losing their hatchlings to fire ant predation. This is especially important if the bird is on the endangered species list, like the black-capped vireo.

- Residential: Pets, children, parents, and the elderly are at risk from the ants’ stings.

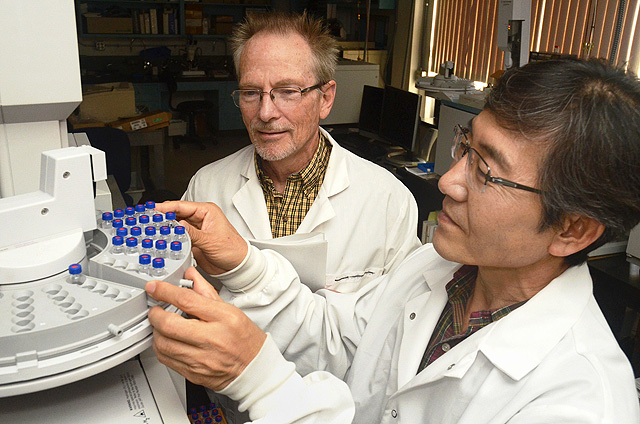

Chemist Robert Vander Meer (left) and entomologist Man-Yeon Choi use gas chromatography-mass spectrome

Chemist Robert Vander Meer (left) and entomologist Man-Yeon Choi use gas chromatography-mass spectrome

UM: What solutions exist right now?

RV: Low-cost treatments are not yet available. Today, the main solutions target the homeowner, because they will pay the high prices of the products found in hardware stores to protect themselves and their children and pets. We need to develop low-cost control methods for farmers and others dealing with the ants on a large scale.

The Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) maintains a quarantine program that inspects shipments moving from fire ant-infested areas to non-infested areas. If fire ants are found, the truck is sent back to the point of origin. This practice is aimed at preventing or slowing the spread of fire ants, but since they are already endemic in large swaths of the country, these measures cannot fully prevent movement of the ants. The most effective barrier to the ants currently is weather – they aren’t physically able to survive colder temperatures, and so have not yet been able to spread beyond certain latitudes. However, as climate change proceeds, fire ants are moving north; it may not be too far in the future that we will find their mounds on the White House lawn.

UM: Why are fire ants such a difficult challenge?

RV: The ants’ area-wide mating flight system distributes hundreds of millions of newly-mated queens back into the infested area and beyond every year. Non-social insect pests are more controllable. However, the sheer numbers involved make the fire ants very, very prolific breeders, and they opportunistically take advantage of a wide range of resources. With an average of 60 colonies/acre in infested areas, the ants need food all the time. The size of the colonies and the chemical (venom) and physical defenses protect the queen from outside interventions, making them, so far, impossible to eradicate.

UM: What research is ARS doing on fire ants?

RV: We have several lines of research exploring different angles of attack. One is to use biocontrol agents such as viruses and microsporidia. Another involves the use of parasites. One parasite, the phorid flies, have been a great success story of the biocontrol effort. Five species have been successfully released into the infested area. The phorid flies put pressure on fire ant populations, decreasing colony worker numbers. They do not directly eliminate fire ant colonies.

We also have two novel, patented pest control methods, each very different from the other. Both are headed for their first field trials soon. The first uses peptides that irreversibly bind to an essential fire ant receptor, which interferes with all life stages of the ant, causing the demise of the colony. This pesticide will not harm pollinators or other non-target insects and is biodegradable. The active ingredients for the second pesticide are inexpensive and if all goes well, may provide some relief for the large-scale needs of farmers.

Fire ants will do anything to resist attack by the tiny phorid fly measuring only about one-sixteenth of an inch. A highly specific natural enemy, the female pierces a fire ant's head and releases an enzyme that later decapitates it. (Photo by Sanford Porter)

Fire ants will do anything to resist attack by the tiny phorid fly measuring only about one-sixteenth of an inch. A highly specific natural enemy, the female pierces a fire ant's head and releases an enzyme that later decapitates it. (Photo by Sanford Porter)

UM: What can homeowners do to control fire ants in their yard?

RV: There are control products that are commercially available. They are effective and can help remove the ants for a time in small-scale settings like a yard. However, their cost makes them too expensive to use on a larger scale. Homeowners also have to continue to re-apply the products, because the ants can re-appear once they’ve been eliminated. This is because of their very robust reproductive strategies, which involve spreading through area-wide massive mating flights, among other features.

UM: What can farmers do if they see fire ant mounds?

RV: There are single mound and small area treatments, but they’re too expensive for most farm settings, though they may work in high value situations – like calving operations. Mounds can be 12 to 20 inches high and very hard if they’re dry, such that farm equipment may be damaged.

UM: Are fire ants present elsewhere globally?

RV: Yes, they have spread to many other areas, and have the potential to continue spreading. Most recently, they were found in Italy and will probably survive along the Mediterranean coast. Japan was infested a few years ago. Australia, Taiwan, China have been infested for decades, and thus far eradication efforts have not succeeded.

Also in our series on fire ants: