Parasitic Ant Species Evaluated Some Years Ago to Control the Red Imported Fire Ant (RIFA) in the US is in Fact a Species Complex with Different Host Associations

By Luis Calcaterra and Andres Sanchez Restrepo

Several years ago Foundation for the Study of Invasive Species (FuEDEI) (then USDA ARS South American Biological Control Laboratory) made a cooperative research agreement with the ARS USDA Center for Medical, Agricultural, and Veterinary Entomology (CMAVE), in Gainesville, Florida. This agreement was aimed at assessing the potential of an inquiline parasitic ant of the highly invasive red fire ants (RIFA, Solenopsis invicta), and black fire ant (BIFA, Solenopsis richteri) (Figure 1). Studies on these parasitic ants in Argentina, which belong to the same genus as its hosts, Solenopsis, revealed that black fire ant populations that hosted the parasitic ant had lower mound densities, fewer queens, and decreased brood production compared to non-parasitized populations. Parasitic queens live attached to the host queen (known as yoking) (Figure 1). The objective of this project was to introduce this parasitic ant among the RIFA populations in the United States to limit colony size and reduce the damage it causes, currently estimated at $7 billion dollars/yr. The parasitic ants have a relatively broad geographic range that coincides with the native distribution of its four known fire ant hosts in Argentina, Brazil, and Uruguay.

The biology of this ant is quite striking: newly inseminated parasitic queens emerge from a parasitized fire ant colony in search of nearby, non-parasitized nests. It is thought that they enter the nest through the refuse pile, which is where the workers throw waste, such as contaminated food. The parasite can then get impregnated with the smell of the volatiles of the host colony in order to pose as a worker of the colony, and escape detection. Another way these parasitic ants can infect new colonies, is when queens from colonies that have more than one queen (polygyne colonies), break away from the original colony along with a group of workers to form a new colony, carrying the parasitic queens with them. The parasitic queens then begin to lay eggs, which are tended by the host workers as if they were their own species (the parasitic ant does not produce workers at all). At one point the weakened host queen can have up to 20 parasitic queens attached, which slowly starves her, or may even decapitate her.

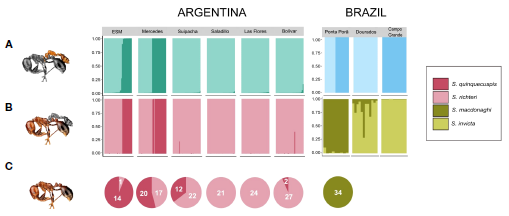

Despite these promising field and lab observations, attempts to artificially rear and transfer this parasitic ant to red fire ant colonies introduced in the USA by CMAVE failed, leading to the suspicion that there was some incompatibility between different groups of parasitic and host ants. To test this assumption, a massive survey was conducted in Argentina and Brazil between 2006 and 2008 by researchers from FuEDEI, CMAVE and the Federal University of Dourados in Brazil (Figure 2), to find and collect a large number of colonies of the four fire ant species parasitized by this inquiline ant. These samples were recently analyzed with modern molecular tools in cooperation with Tennessee University, which revealed that the samples were in fact comprised of four closely related groups that are probably different species impossible to tell apart with traditional methods (called cryptic species), each with different species of host fire ant (Figure 3). This information may lead to refloat this project, now with a better knowledge of the subtleties that regulate host-parasite relationships.

For more information, see: Dekovich A, Ryan S, Bouwma A, Calcaterra L, Silvestre R, Staton M and Shoemaker D (2023) Population genetic analyses reveal host association and genetically distinct populations of social parasite Solenopsis daguerrei (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Front. Ecol. Evol. 11:1227847. doi: 10.3389/fevo.2023.1227847

Figure 1. Left, RIFA and parasitic ant queens; right, BIFA and two parasitic ant queens hooked by their jaws to the host queen

Figure 2. Brazil and Paraguay survey.

Figure 3. Structure plots for (A) the parasitic ant, and (B) hosts across the sampled range. Number of unparasitized nests of each host species (C)

For inquiries regarding this article contact: info@fuedei.org.

The Foundation for the Study of Invasive Species (FuEDEI), formerly known as the South American Biological Control Laboratory (SABCL), is located in Hurlingham, Argentina, near Buenos Aires. The SABCL/FuEDEI plays a crucial role collecting and providing candidate biological control agents for South American weeds and pest insects for federal and state cooperators, several U.S. universities, and research collaborators worldwide since 1962. FuEDEI’ s main mission includes exploring for natural enemies of target insects and weeds in Argentina and neighboring countries and conducting host-specificity testing to determine their safety for eventual release in the U.S. In addition, complementary research that investigates the ecology, behavior, taxonomy, and genetic differences based on geographic distribution is conducted on both targets and potential agents. Performing these studies in the region of origin of the target pest serves as an efficient prescreening process that reduces the number of biocontrol agent candidates shipped. This reduces the amount of quarantine work and valuable quarantine space occupation, the expenses related to permitting processes, the risks of escapes, and the release of maladapted or wrongly identified agents to a minimum, saving in costs and hazards. On some occasions these complementary studies help us understand why an exotic organism becomes invasive, which can, in turn, lead to determining novel strategies for their management.