| FG Behavior |

|

Field Guide to Common Western Grasshoppers: Seasonal Occurrence and Behavior

by Robert E. Pfadt

List of Species Fact Sheets (60 Species)

Seasonal Cycles

An important component of grasshopper life history is the seasonal cycle - the timing of the periods of egg hatch, nymphal growth and development, emergence of the adults and acquisition of functional wings (fledging), and the deposition of eggs or reproduction. The occurrence of these periods varies among the species and is greatly influenced by weather. An early spring hastens these events and a late one delays them. Latitude also influences the dates of occurrence. In North America springtime comes earlier in the south and later in the north. Consequently, hatching, development and maturation come earlier in the south and later in the north. In the West, altitude is also an important factor. The lower temperatures of higher altitudes, especially those of mountain meadows, are responsible for retarded seasonal cycles of grasshoppers and may often cause a two-year life cycle among species that ordinarily have a one-year life cycle.

Nymphal and adult grasshoppers are present all year long in natural habitats. Several species overwinter in late nymphal stadia and become adult in early spring. The majority, however, pass the winter as eggs protected in the soil. Depending on the species, these eggs hatch at different times from early spring until late summer. The variety of seasonal cycles allows actively feeding and developing grasshoppers to spread out over the entire growing season. Each species has its own time to hatch, develop, and reproduce, but with much overlapping of the cycles. An experienced scout going into the field to survey expects to find certain species at certain times and is thus aided in making identifications. Table 5 arranges the seasonal cycles of grasshoppers into: (1) very early nymphal and adult group, (2) very early hatching group, (3) early hatching group, (4) intermediate hatching group, and (5) late hatching group. The table is especially helpful in the identification of young nymphs.

|

TABLE 5. Species of grasshoppers grouped by seasonal appearances. |

||

|

SLANTFACED |

BANDWINGED |

SPURTHROATED |

|

Early spring, large nymphs and adults. Overwintered in nymphal stage. |

||

|

Eritettix simplex |

Arphia conspersa |

. |

|

Very early hatching group, hatching in early spring. |

||

|

Aeropedellus clavatus |

. |

Melanoplus confusus |

|

Early hatching group, hatching in mid-spring. |

||

|

Acrolophitus hirtipes |

Camnula pellucida |

Aeoloplides turnbulli |

|

Intermediate hatching group, hatching in late spring. |

||

|

Aulocara femoratum |

Derotmema haydeni |

Hesperotettix viridis |

|

Late hatching group, hatching begins in early summer. |

||

|

Eritettix simplex |

Arphia conspersa |

Dactylotum bicolor |

Behavior

A grasshopper's day (and night) are linked closely with the physical factors of the environment, especially temperature, but also light, rain, wind, and soil. Stereotyped and instinctive behavior patterns serve grasshoppers remarkably well in making adjustments to wide fluctuations of physical factors that otherwise might be fatal. Grasshoppers effectively exploit the resources of their habitat and at the same time are able to tolerate or evade the extremes of physical factors. Their characteristic rapid jumping and flying responses help them escape numerous enemies that parasitize or feed upon them.

In temperate North America, certain behavior patterns are held in common among grasshopper species, especially among those occupying the same part of the habitat, while other patterns differ. Individuals of different species have different ways of spending the cool nights. Some retreat under litter or canopies of grasses; others squat on bare ground and take no special shelter. Still others may climb a small shrub or a tall grass plant and rest at various heights within the canopy. Under favorable conditions of temperature and other elements of weather, grasshoppers may be active and even feed during the night. In southwestern states they have been observed on warm nights wandering about on the ground and on vegetation, feeding, and stridulating. Several species have been recorded flying at night and are attracted to city lights. A temperature of 80°F is apparently a prerequisite for night flying with maximum flight activity occurring at temperatures above 90°F.

A grasshopper's day usually starts shortly after dawn. Because body temperatures have fallen during the night, a grasshopper on the ground crawls to an open spot, often on the east side of vegetation, that allows it to warm itself by basking in the radiant rays of the sun. A common orientation is to turn a side perpendicular to the rays and lower the associated hindleg, which exposes the abdomen. Those that have spent the night on a plant make adjustments in their positions to take advantage of the sun's rays or they may climb or jump down to the ground to bask. Although grasshoppers generally remain quiet while they bask, they occasionally stir, preen, turn around to expose the opposite side, and sometimes crawl to a more favorable basking location. Grasshoppers may bask for a second time in the cool of late afternoon. Then as shadows begin to engulf the habitat, they retreat into their customary shelters.

After basking for one to two hours on sunny days, grasshoppers become active. They may walk about, seek mates, or feed. Because grasshoppers are cold-blooded creatures, their usual daily activities are interrupted when the weather turns cold, overcast, or rainy. During such times they generally remain sheltered and inactive.

During warm sunny weather of late spring and summer, grasshoppers take advantage of two foraging periods, one in the morning and one in the afternoon. Different species of grasshoppers have different ways of attacking and feeding on their host plants. Individuals of certain species climb the host plant to feed on leaves, petals, buds, or soft seeds while others cut and fell a grass leaf and feed on it while sitting on the ground. Geophilous (ground-dwelling) species regularly search the ground for food, picking up and feeding on seeds, dead arthropods, and leaves felled by other grasshoppers. In grasslands with considerable bare ground, very little litter is produced by grasshoppers. Severed leaves, dropped by the grasshoppers that feed on the host plant, are soon found and devoured by the ground foragers. In habitats infested by dense populations of grasshoppers, pellets of their excrement, rather than litter, accumulate in small conspicuous piles. Only in habitats of tall grass do grasshoppers produce leafy ground litter that goes uneaten and "wasted." This is because the grasshopper species in these habitats are phytophilous and feed resting on the host plant.

Grasshoppers fastidiously select their food. By lowering their antennae to the leaf surface and drumming (tapping) it with their maxillary and labial palps, grasshoppers taste a potential food plant. Gustatory sensilla located on the tips of these organs are stimulated by attractant and repellent properties of plant chemicals, allowing a grasshopper to choose a favorable host plant and reject an unfavorable one. A grasshopper may take an additional taste by biting into the leaf before it begins to feed freely. Phagostimulants are usually important ones nutritionally-certain sugars, phospholipids, amino acids, and vitamins. Grasshoppers may even make choices among the leaves of a single host plant. They prefer young green leaves and discriminate against old yellowing ones. Nevertheless, individuals of ground-dwelling species often feed in short bouts on old plant litter lying on the ground as well as on dry animal dung. This feeding may be a means of restoring water balance - either losing or gaining moisture.

Later, in the species fact sheets, grasshopper food plants are referred to by their common names. The appendix (Grasshopper Food Plants) provides a listing of these with their scientific names to clarify any ambiguities.

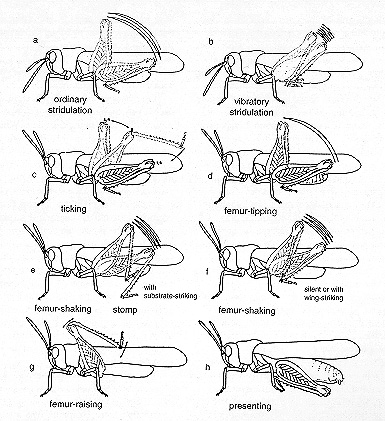

Amazingly, grasshoppers are able to communicate visually and acoustically among themselves. They produce sounds with structural adaptations on hindlegs and wings and receive these signals with auditory organs (ears) located in the first abdominal segment (Fig. 8). Using their colorful wings and hindlegs they also flash visual messages and receive these with their compound eyes. Intraspecific communication, that which occurs between members of the same species, is used to attract and recognize mates, to ward off an unwanted suitor, and to defend a territory or a morsel of food. Grasshoppers produce acoustical signals by rubbing the hindlegs against the tegmina (Fig. 12) or the sides of the abdomen. They may also communicate by rapidly flexing or snapping their hindwings in flight, a behavior called crepitation. Each species apparently produces its own unique sound and, in human terms, has its own language. The details, where known, of finding a mate are described in the species section of this guide.

Figure 12. Signals and postures commonly occurring in grasshoppers: (a) ordinary stridulation -- a slow, stereotyped, repetitive or non-repetitive, high amplitude movement in which the femur rubs against the forewing; (b) vibratory stridulation -- a fast, stereotyped, repetitive, low amplitude movement in which the femur rubs against the forewing; (c) ticking -- a stereotyped, repetitive or non-repetitive movement in which the tibiae are kicked out and struck against the ends of the forewings; (d) femur-tipping -- a silent, stereotyped, non-repetitve raising and lowering of the femora; (e) Femur-shaking (with substrate-striking) -- a stereotyped, repetitive shaking of the femora in which ends of the tibiae strike the substrate to produce substrate vibration or a drumming sound; (f) femur-shaking (silent or with wing-striking) -- similar to (e) but the movement is silent, or the femora strike the forewings; (g) femur-raising -- a slow, graded non-repetitive movement that may or may not be accompanied by mild upward kicking motions of the tibiae; (h) presenting -- a variable, graded posturing of the female in response to male courtship, in which the end of the abdomen is made more accessible to the male by lowering both the end of the abdomen and the hindlegs. (Courtesy of Otte, 1970, Misc. Publ. Mus. Zool., Univ. Michigan, No. 141.)

Oviposition behavior differs among species of grasshoppers. Most species lay their eggs in the ground. Females of some species choose bare ground, while others choose to lay among the roots of grasses or forbs. A female ready to lay often probes the soil several times before finally depositing a clutch of eggs. Experimental evidence indicates that probing is a means by which a female obtains sensory information on the physical and chemical properties of the soil. The ovipositor is supplied with a variety of sensilla that allow a female to monitor soil conditions. Temperature of the soil must be favorable, water content must be in a suitable range, and acidity and salt content of soil must be tolerable. Females of some species select loose soils such as sand, some rocky soils, while the majority of females prefer compact loamy soils for oviposition. The pods of different species vary in size, shape, and depth in the soil. The latter condition profoundly affects incubation temperature, hatching, and egg survival.

A female actively depositing eggs is often attended by one or more males. Depending at least partly on clutch size, females take from 25 to 90 minutes to lay a full complement of eggs. After withdrawing her ovipositor a female will take a minute or two to cover the aperture of the hole with particles of soil and ground litter. The female uses either her ovipositor or her hind tarsi, depending on species, to do this. The act appears to be instinctive maternal care that provides some protection for the eggs from predation by birds, rodents, and insects. In certain species, as soon as the female retracts her ovipositor, the attendant male mates with her; females and attending males of other species merely walk away from each other.

Grasshoppers have different ways of avoiding excessively high temperatures that may occur in summer for a few hours each day. When ground temperatures rise above 120°F, individuals of certain species climb plants, some to a height of only 2 inches on grass stems, others climb higher (5-12 inches), and some even higher on tall vegetation such as sunflower in the southern mixedgrass prairie or a tall cactus plant in the desert prairie. In these positions individuals usually rest vertically with the head up on the shady side of the plant. Many ground-dwelling species first raise up on their legs or stilt, but as temperatures rise further, they crawl into the shade of vegetation. Individuals of other ground-dwelling species may stilt, then move away from the hot bare ground and climb on top of a short grass such as blue grama. They face the sun directly so that the least body surface is exposed to the radiant rays. In this orientation the grasshoppers are 1 to 2 inches above ground and rays of the sun strike only the front of the head.

Characteristic behavioral responses regularly observed by grasshopper scouts and collectors of insects are the jumping and flying of grasshoppers, apparently to escape capture. The stimuli initiating these responses may be of many kinds but circumstantial observation indicates that movement of the collector's image across the compound eye is usually the primary stimulus. One may noisily push a stick on the ground close to an individual without eliciting a response. Also other insects, such as large darkling beetles or large grasshoppers, may crawl close and elicit no response until they touch a resting grasshopper. Phytophilous species of grasshoppers may not jump or fly to escape intruding scouts and insect collectors, but may shift their position away from the intruder to the opposite side of a stem, retreat deeper into the canopy, or drop to the ground. Collectors and scouts entering the habitat of dense populations of grasshoppers may get the impression of continuous movement by these insects, but investigation of their time budgets indicates that during most daylight hours they are largely quiescent (46 to 80% of the time). Considerably less time is devoted to feeding, locomotion, mating, and oviposition.

The adults of most species of grasshoppers possess long, functional wings that they use effectively to disperse, migrate, and evade predators. Adults regularly fly out from deteriorating habitats caused by drought or depletion of forage, but they may also leave a site for other reasons. Some individuals of a population instinctively fly and disperse while others remain in the habitat. The most notorious migrating grasshoppers are Old World locusts, Schistocerca gregaria and Locusta migratoria. Several species of North American grasshoppers are likewise notable migrators: Camnula pellucida, Dissosteira longipennis, Melanoplus sanguinipes, M. devastator, M. rugglesi, Oedaleonotus enigma, and Trimerotropis pallidipennis.

Past direct observations of grasshoppers in their natural habitat have revealed various behavioral responses among species. Each appears to have its own way of reacting to a battery of environmental factors. Because a relatively few species have been investigated, much remains to be discovered. The whole subject of grasshopper behavior provides a fertile area for research both in the field and in the laboratory. Acquiring sufficient information on the various aspects of grasshopper behavior will not only serve to improve integrated management of pest species and the protection of beneficial ones, but will also advance the science of animal behavior. Numerous observations of the behavior of common western grasshoppers have been made during the course of this study. Results of these observations are reported later in the treatment of individual species.